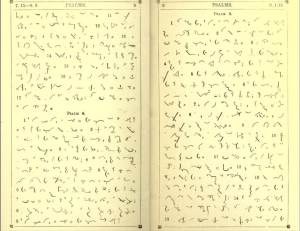

The Book of Psalms in the Corresponding Style of Pitman’s Shorthand

More religion and stenography, this from Isaac Pitman’s A Manual of Phonography, or, Writing by Sound (1864):

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the principles of the Reformation were extensively promulgated in this country from the pulpit. A desire to preserve for future private reading the discourses of the principal preachers of that day, led to the cultivation of the newly invented art of shorthand writing. Teachers and systems increased rapidly; and by a comparison of one mode with another, and by experimenting with various series of alphabetical signs, Mason, at length produced a system of the art, from the publication in 1588 of Brights’s system of arbitrary characters for words (or rather from the publication of the first shorthand alphabet by John Willis, in 1602) to the appearance of Mason’s system in 1682, may therefore be considered as resulting from the dawn of RELIGIOUS FREEDOM. Mason’s system was published by Thomas Gurney, in 1751, and it is used by members of his family, as reporters to the Government, to the present time (17).

So, on the one hand, because the “desire to preserve … the discourses of the principal preachers of the day” required a mode of recording faster and more efficient than normal writing, our knowledge of the Reformation depended on the development of shorthand writing systems. On the other hand, though, the rapid increase of shorthand writing systems and schools in the 16th and 17th centuries also points to the idea that shorthand writing was a product of the Reformation. So shorthand and “RELIGIOUS FREEDOM,” in Pitman’s account, sort of produce each other.

This seems like a dubious empirical claim, but there’s something about it that I don’t want to let go of. After all, we’re now used to talking about how new technologies enable the transmission and circulation of ideas that have real effects in the world (the Arab Spring and Twitter, for example). But the idea of print and the printing press dominates the way we imagine that information circulated basically until the invention of the telegraph. (I’m ignoring the work of many important scholars, like Lisa Gitelman and Bernhard Siegert, but stay with me.)Â Pitman may offer a hyperbolic, slightly dubious account of the Reformation’s media ecology, but in doing so he forces us to imagine a world in which the means by which information, language, and ideas made their way from one medium to another, from the voice of a speaker to the eyes or ears of a distant reader or listener, were not so settled.

In Deep Time of the Media, Siegfried Zielinski urges us to recapture those lost possibilities that inhere in forgotten or vestigial media. He argues that progressivist models of media history view our present media environment as developing inevitably out of prior environments. In this view, “history is the promise of continuity and a celebration of the continual march of progress in the name of humankind” (3). This progressivist idea of history is, in truth, ahistorical, since it suggests that, “everything has always been around, only in less elaborate form. One needs only to look” (3). Media historical progressivism remains blind to the possibilities offered up by media and technologies that didn’t survive, that remain buried. It is these forms that Zielinski finds interesting, urging us not to “seek the old in the new” but to “find something new in the old” (3).

The history of shorthand offers this kind of new oldness, but the relation between past and present, new and old in shorthand is more dialectical than what Zielinski suggests. I do see in Pitman the echo of an older way of thinking about the metaphysics of the voice’s relation to the hand and a foreshadowing of media history to come. Pitman’s enthusiasm about shorthand’s entwinement with political and religious liberation could easily transform into its opposite. Where he saw the shorthand as an agent of freedom, we could also see the origins of the copyist as a mechanized drudge. I’m still not settled on how I think all this plays out. Maybe it’s all because Pitman was a Swedenborgian.

Recent Comments